This text is a consideration of recent high-profile cases of cinema and television, HBO’s Chernobyl, Netflix’s Stranger Things, Ari Aster’s Midsommar and others, that might offer insight into the elongated controversy surrounding Netflix series 13 Reasons Why. It is written from my perspective in humanities as a researcher studying suicide’s visual cultural representations.

HBO’s acclaimed miniseries Chernobyl (2019) starts with the suicide of its male protagonist, Soviet era scientist Valery Legasov (Jared Harris). The self-willed death ends a sequence with the scientist, held in custody, reciting his memoirs of the governmental cover-up leading to the disastrous near-meltdown of the nuclear reactor at Chernobyl. “What is the cost of lies? It’s not that we’ll mistake them for the truth?,” he recites the central question of the series to his tape recorder. After having finished his account, he hides the cassettes from the KGB at the disguise of taking out the trash, and — back at his apartment — smokes one last cigarette, places enough milk bowls on the floor for his cat to survive over few days, checks his watch and then steps into the void, hanging himself at the exact moment of the power plant accident two years earlier. His suicide, that both opens and closes the series, intimates an honourable scientist’s despair in a rotten system as well as marks his resistance to it. In the series’s diegesis his death also gains strategic visibility to his cause: revealing the truth suppressed by the Soviet government so that similar nuclear plant accidents might be avoided in the future.

In another streaming service, Netflix, the third season of sci-fi series Stranger Things (2019) closes with the remaining characters mourning the loss of two central male characters, Billy and Hopper. Both sacrifice themselves in the season’s last episode in order to stop The Mind Flayer, the transmuting monster of the series, taking over the little town Hawkins, and thus reiterate the heroism of Eleven (Millie Bobby Brown), the girl-protagonist, in the series’ first battle against The Mind Flayer at the end of the first season. In an earlier blog-post, I considered this scene’s glorified iconography, which fitted into the cinematic regime of sacrificial “altruistic” suicides, often separated from the so-called suicides proper, or “egoistic” suicides.(1) These sacrificial deaths are often gendered masculine in western popular culture, so as a young female character’s action Eleven’s pseudo-death catched eyes as unusual. In the third season’s closure, however, the “gender of sacrifice” has been restored, similarly to the aforementioned Chernobyl where the male protagonist’s suicide (this time egoistic, although bearing some of the glory of sacrifice in addition to his despair) marks his integrity at the face of Soviet government’s fatal lies. Billy, swayed by the evil, redeems himself with his voluntary death, whereas Hopper’s self-sacrifice is a that of a wholehearted family man.

On the silver screen instead, after these two examples of television, Ari Aster’s horror film Midsommar (2019) starts with the female protagonist Dani (Florence Pugh) panicking over an alarming email sent by her bipolar sister. The sister has, as is soon releaved, committed a murder-suicide with exhaust fumes, leaving Dani orphaned at the death of her entire family. This shocking and violent death serves as the backdrop of the trippy film’s psychological horror, as the thematics of disenfranchised mourning, of grief that cannot be grieved, (2) manifest throughout the film. The suppressed sorrow, related to the stigmatized death of suicide also in real life, follows Dani from the US to Sweden, where she participates the exotic midsummer festivities with her boyfriend and his buddies. Here we see Dani, haunted by unwanted images of her family’s death, swallowing her sorrow in her dysfunctional relationship and her detached social encounters only to eventually let the suppressed emotion erupt at the strange rituals of the Hårgan cult she is being incorporated into.

Suicide is in Midsommar connected to mental illness, yet also to pagan faith, as it features in the Hårgan rituals as an altruistic death; as a death setting the social collective above the individual. Unlike Chernobyl’s or Stranger Things‘s individual deaths however, it remains fearful rather than glorified, as it is connected to strangeness through both mental illness and cultist mentality, and through the film’s distancing of the ritual suicide to “exotic Sweden”. Yet if in these aspects Midsommar, like most audio-visual culture, partakes in suicide’s marginalization as something no “sane” individual would think or commit (unless endowed with the mentioned sacrificial quality, which renders the death as something more than the regular “murder of self” referred with the concept “suicide”), the movie appears to witness the need to connect and mourn. It also appears to take a tentatively non-judging stance towards some of the individual deaths depicted in the film. After all, for the protagonist Dani the permission to feel (and to belong), withheld in her country of origin yet given to her by the Hårgans, who indifferently kill both themselves and others, imply a happy end in a similar sense The Wicker Man‘s (1973) ritual murder does: in this influential predecessor to Midsommar the conservative protagonist Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) suffers an immolation in a ritual fire, which is similarly ambiguous as a death renewing the social collective in the universe of the film.

All three instances of audiovisual culture from summer 2019 are quite interesting in their depiction of suicide, whose cinematic representation and regulation is my main interest in my research. Unlike is often thought of the tabooed death, popular culture featuring suicide is far from low-profile or hard to find. For instance, next to these aforementioned high-profile examples, that serve my essay as random encounters rather than as closely picked illustrations, HBO recommends the viewers of Chernobyl to follow it up with another mini-series Sharp Objects (2018), an acclaimed narrative of female self-harm and violence based on Gillian Flynn’s study of female monstrosity in her novel of the same name. And right after pushing out the third season of Stranger Things, focused on everyman characters’ death-defying heroism, Netflix has released the third season of 13 Reasons Wh, it’s controversial first season (2017) similarly known for the link drawn between mental illness, sexual violence and girlhood self-harm to Sharp Objects, and similarly to Midsommar following the protagonist’s (this time: male’s) recovery from a state of suicide’s disenfranchised mourning.

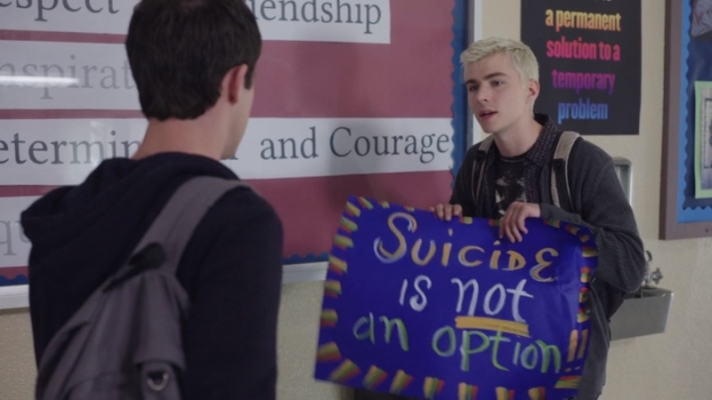

Of course, 13 Reasons Why, based on Jay Asher’s novel of the same name and narrating the reasons for a sexually assaulted young girl’s (Katherine Langford) suicide through 13 cassette tapes delivered to her peers and her could-have-been-sweetheart Clay (Dylan Minnette), has occupied headlines ever since its premier. It has done so also recently, after the makers’ decision to first cut out the first season’s suicide scene and then to cancel the series after the fourth season, scheduled to come out 2020. In the series’s publication in spring 2017 several agents, from mental health experts to parents and suicide survivors, criticized the series for its romanticization of suicide, for the triggering nature of the graphic rape and suicide scenes, and for the downplaying of the role of mental health and recovery, among other factors. The decicision, that follows this discussion, is based on a recent paper reporting an increase in the suicide rates among American boys aged 10-17 after the release of the first season of 13 Reason Why. (3)

What might these examples tell us of the representation of suicide? Firstly, although the controversy surrounding 13 Reasons Why since its premier to this day, speaking of the sensitive nature of this death, might not imply, audio-visual popular culture’s representations of self-willed death are many and everywhere. Secondly, in looking at their quality, these representations are often differentiated from one another as glorified and demoted deaths, (4) that are often repetetive of similar gendered myths about heroism or self-killing. Often these two are conceptually differentiated as “sacrificial deaths” and “suicides”, where their evaluation follows the Durkheimian line dividing “altruistic” suicides commited for, or ordained by, the social collective from the domain of more individualistic “egoistic” suicides, yet their glorification/demotion also has a clear gendered aspect.

In my excerpts, for instance, we can witness self-willed death’s gendering in stories about heroic agency and victimhood: the deaths endowed an amount of glory as deaths with which something admirable is achieved, are almost without exception gendered masculine (and connected to male agency), (5) as in Chernobyl or in Stranger Things‘s latest season. The ones that do not so easily cross the edges of glory are instead often victimized in survival stories bearing allusions, if not explicit diagnoses, to the vague umbrella category of “mental illness”, like in Sharp Objects (or 13 Reasons Why) where alcoholism and depression, related to sexual abuse, represent the more understanding siding of suicide and self-harm with mental illness. In these kinds of portrayals the suiciding character can also be male, yet on-screen suicides thus “passivized” are more commonly connected to female characters and attributes. (6)

Horror film Midsommar (although ambiguous in its moral stance), instead represents the harshest side of suicidal mental illness’ representation in its amount of shock value, as it associates to both psychopathology and murder through which it gains terrifying agency, and is visually depicted through the domain of “the disgusting”. As mentioned, the representation here is particularly marginalizing in its depiction of difference, but also most “medicalizing” representations of suicide could be seen to be that as normative discourses about anormalcy.

The aforementioned instances of recent audio-visual popular culture also offer a tool with which to comment the controversy surrounding 13 Reasons Why and its suicide scene (again, for I have written about the controversy also in this finnish-language blog post when it first arose). They could be seen to imply that in many senses — such as in its gendering take on suicide and in its storyline of depression — also 13 Reason Why‘s controversial depiction of voluntary death is a fairly “tame” or “conventional” one, even if it has been singled out as particularly dangerous. And although the discussion surrounding the series has targeted in particular the series’s argued romanticization of suicide, it is quite conventional even in this aspect especially when the whole range of self-willed death’s representations are considered. It could even be considered less glorifying than for instance the honorable suicide of the lone scientist in Chernobyl. Why the series stands out is mostly because it is a high-profile drama starring a suiciding female protagonist whose diagnostic death is rationalized through the titular thirteen reasons. Although the controversy, and the eventual deletion of the suicide scene, are based on certain issues with the series, its reception is also heavily value-laden and gendered.

In its pronounced core issues, suicide’s romanticization and its representation as a death “resulting from reasoned action“, that in particular the criticism of the muted role of medical diagnoses and solutions represents, the removal of the graphic suicide scene two years later does not remove the problem pointed out by the series’s critics. In digital culture, the decision to censor the scene after years of streaming is also more symbolic than pragmatic: it mostly makes a point and sets an example for what kind of representations of the sensitive death are to be avoided and censored in the future, since the controversial content has in this instance already spread from its original context to become an unerasable part of the social media fabric. This position — that of a precedent — motivates me to speak in defence of the series’s representation again, although it is never uncomplicated to take a stance for something accused of inseminating death among young people, even when this causality is in the category of “we do not know for sure” and the grounds for the controversy problematic.

As mentioned, in this occasion the decision to remove the suicide scene follows a reported increase in the suicide rates among American boys aged 10-17. Yet it also responds to suicide’s tabooed position. In particular it does so in the first season’s criticism of suicide’s presentation as something other than “irrational,” which proposes an anomalous position for the death historically viewed as dangerous. I have studied the connection between taboo and the series’ reception further in my Finnish-speaking article, (7) where I discuss the similarities between this anthropological structure, relying on fears of contagion in its domestication of cultural threaths, and “suicide contagion”, the phenomenon studied by sosiologists, psychologists and public health scientists affecting also 13 Reason Why’s reception and cricitism. (8) The censorious reception is based on fear more than studied fact, and also inseminates those fears further — of the “inexplicable death” and of this death’s representation’s “media effects,” which too easily take the form of the hypodermic needle theory, where audiences are seen as mere non-autonomous victims for media’s messages. The actions based on the criticism of suicide’s presentation without explicit labels of mental illness also seek to normalize suicide’s presentation as a shameful, silenced condition, as they marginalize self-harm and suicidal thoughts by presenting them as anomalies of the mind enacted by individuals diagnozed as different.

These theories related to fictitious suicide’s feared copy-cat effect are not uncontested in the scientific field. (9) As also the commentaries following the removal have noted, the correlation between a fictitious representation and an increase in real-world suicides does not necessarily imply a causality. (10) Studies such as these are particularly complicated and here continue to provide conflicting results. (11) In this instance, the reported increase in boys’ suicides also defies the tentative models where suicidal imitation has been explained with gendered identification with the suiciding character. (12) Some recent studies (although they have studied the joint effect of the first two seasons of the series) have even seen 13 Reasons Why to decrease thoughts related to harming or killing oneself (13), as well as to increase empathy in its viewers and augment respondents’ willingness to discuss mental-health issues with others. (14) The series is thus not so simply detrimental, and there might be also other reasons for the reported increase in suicides other than 13 Reasons Why or it’s graphic scene featuring a female protagonist’s self-willed death. For instance, the series features also victimized male side-characters considering or attempting suicide, and their representation is closer to “egoistic suicides’s” conventional passivizing and instrumental representations.

The controversy surrounding the series has been beneficial in that it has opened a discussion about suicide, mental illness and their on-screen representations. Depictions of suicide fill our screens in uncountable numbers and not all of them survive the daylight as “ethical” — not even 13 Reasons Why, which troubles also me in some of its guilt-tripping and spectacular aspects and in particular in its soundtrack selection for the suicide sequence. Yet it is alarming to see this series, not only listing an amount of understandable reasons for the still stigmatized death but also witnessing their accumulation to the point where life’s hardships start to feel unbearable, made a warning example in the elongated controversy surrounding it. I see the series’s detailed narration of suicide’s reasons from first-person perspective also as an asset, not as a simple threat, because in doing so it offers such understanding on self-willed death that individuals struggling with suicide, its stigma and taboo might need. In particular in considering discursively constructed shame’s relationship to self-willed death, (15) it would feel important not to merely condemn but also to support the series’s dramatic representation of suicide as it does not marginalize and stigmatize the condition as many others do, but instead seeks to understand it.

It must be added my point of view in this essay is affected by my background in studying suicide’s representations from the perspectives of humanities and visual culture (and theories of related to suicide’s tabooed status), which give a different perspective also to estimating the possible effects of suicide’s representation. In opposition to a background in the medical sciences my gaze is not affected by focus on representations’ direct effects, but rather on suicide’s narrative uses and on how our popular discourses shape how self-willed death and suicidal individuals are perceived and understood, which can affect the lived reality also indirectly and through the accumulation of (various kinds of) representations. For this reason I’m not often worried of single instances of media representation, but rather of the wider popular cultural trends in which suicide is treated — thus taking a social-constructivist approach to the topic, which sees lived reality shaped by our reiterating (and often affective) interpretations of it.

From this perspective 13 Reasons Why here also offers a welcome balance to the existing conventions in few different senses. More often than understandingly told through a protagonist, suicide is in Western popular culture reduced into it’s shock value (as is no doubt done also in horror film Midsommar, despite the ambivalence that can be read out of it). In some cultural theories (interesting also me in my work) death’s treatment in such “pornographic” representations focusing on violent death has been feared to lead to the almost fictitious nature of death (suicide included) in a culture distanced from the realities of dying and death. (16) Death’s fictivization is hinted, for instance, in the Logan Paul controversy, January, 2018, when the high-profile YouTube vlogger caused outrage in joking at the expense of a real-world suicide victim found in Aokihagara, the Japanese “suicide forest” often exotized in white fiction as horror film trope. Joking at the expense of a suicide victim takes a certain level of suicide’s and suiciding individuals’s dehumanization, and their constant othering, marginalization and suicide’s instrumentalization as a narrative ploy (opening, closing and changing the direction of our audiovisual narratives) in Western popular culture could be seen to contribute to this.

For same reasons I also continue to be thoughtful of the gendered and medicalized representative regime which more often passivizes egoistic suicide on screen as (quite often feminine) mental illness rather than studies its reasons and the agency it also takes to take ones life, so as to make suicide so “effeminate” a sign of divergence, that when a culprit for a real-world suicide can be found from a female monster instead of a male suicide, it becomes strangely easy to accuse a living, breathing teenage girl of murder in one of our mediatized scapegoat rituals. Next to Chernobyl and Sharp Objects, HBO has recently published a two-piece documentary on the Death of Conrad Roy, I Love You, Now Die: The Commonwealth vs. Michelle Carter (2019), which offers an interesting and quite unique example not only of suicide’s on-screen romanticization but of how the conceptions circulated in our portrayals of suicide (closely intervowen with our conventions for representing gender) are reflected in a legal case against a 17-year-old girl for inciting her depressed boyfriend to kill himself.

I came to write this text in order to think with the recent representations and media events related to representing suicide, the latest turns with the Netflix-series’s 13 Reasons Why being one of them. Closing with these two media events, the Logan Paul controversy and the mediatization of the death of Conrad Roy, is a way of thinking with these materials without anything certain to say, but also a way to state there are also more questions related to representing suicide aside the feared media effects that have been requiring column space in the controversies surrounding the single demonized instance of 13 Reasons Why.

Some references:

[1] Émile Durkheim, Suicide: A Study in Sociology (The Free Press: New York, 1966).

[2] Kenneth J. Doka, “Disenfranchised grief,” Bereavement Care vol. 18, No. 3 (1999): 37-39.

[3] Jeffrey A. Bridge et al, ”Association Between the Release of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why and Suicide Rates in the United States: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis,” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 28.4.2019.

[4] Stephen Stack and Barbara Bowman, Suicide Movies: Social Patterns 1900–2009 (Toronto: Hogrefe, 2012).

[5] e.g. Michele Aaron, Death and the moving image: ideology, iconography and I (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014).

[6] Heidi Kosonen, “Hollywoodin nekromanssi. Naisen ruumiiseen kiinnittyvä itsemurha elokuvien sukupuolipolitiikkana,” Sukupuoli ja väkivalta: lukemisen etiikkaa ja politiikkaa, edited by Sanna Karkulehto & Leena-Maija Rossi (Helsinki: SKS, 2017): 95–119.

[7] Heidi S. Kosonen, “Itsemurhatartunnan taikauskosta: The Moth Diaries (2011) ja 13 Reasons Why (2017)” Tahiti, no. 2 (2018): 34-49.

[8] David J. Phillips, “The Influence of Suggestion on Suicide: Substantive and Theoretical Implications of the Werther Effect,” American Sociological Review vol. 39, no. 3 (1974): 340–54.

[9] Gijin Cheng et al, ”Suicide Contagion: A Systematic Review of Definitions and Research Utility,” PLoS ONE vol. 9, no. 9 (2014): 1–9.

[10] Alan L. Berman, “Fictional depiction of suicide in television films and imitation effects,” The American Journal of Psychiatry vol. 145, no. 8 (1988): 982–85.

[11] James N. Baron and Peter C. Reiss, “Same Time, Next Year: Aggregate Analysis of the Mass Media and Violent Behavior,” American Sociological Review vol. 50, no. 3 (1985): 347–63; James B. Hittner, “How Robust is the Werther Effect? A Re-examination of the suggestion-imitation model of suicide,” Mortality vol. 10, no. 3 (2005): 193–200.

[12] Benedikt Till et al, “Who Identifies with Suicidal Film Characters? Determinants of Identification With Suicidal Protagonists of Drama Films,” Psychiatria Danubina vol. 25, No. 2 (2013): 158-162.

[13] Florian Arendt et al, “Investigating harmful and helpful effects of watching season 2 of 13 Reasons Why: Results of a two-wave U.S. panel survey,” Social Science & Medicine vol. 232, July (2019): 489-498.

[14] “Exploring how teens, young adults and parents responded to

13 Reasons Why,” Report by Northwestern: Center on Media and Human Development, March 2018.

[15] e.g. Barry Lyons and Luna Dolezal, “Shame, stigma and medicine,” Medical Humanities vol. 43, no. 4 (2017): 208–10; D.H. Buie and J.T. Maltsberger, ”The Psychological Vulnerability to Suicide,” Suicide: Understanding and Responding, edited by D. Jacobs and N. Brown (Madison: International Universities Press, 1989), 59–71.

[16] e.g. Geoffrey Gorer, “The Pornography of Death,” Encounter, October (1955): 49-52; Jon Stratton, “Death and the Spectacle in Television and Social Media,” Television & New Media, November (2018).

Toinen artikkeli, “Pyhän lapsuuden paljastama tabu : näkökulma Sami Saramäen Tom of Finland -muumeihin ja Dana Schutzin Open Casket -maalaukseen,” on puolestaan näkökulma kahteen keväällä 2017 pilkahtaneeseen kuvakiistaan. Sekä huhtikuun Image-lehden “Moomin of Finland” -tapausta, joissa muumihahmot kohahduttivat Sami Saramäen piirtämissä kansikuvissa Tom of Finland-henkisinä, että Dana Schutzin kevään Whitney biennaalissa esitettyä, rodullista väkivaltaa kommentoinutta maalausta Open Casket (2016) yhdisti lapsen figuuri, johon olen väitöskirjassani ankkuroinut tabua. Artikkeli on luettavissa avoimesti verkossa, täällä TAHITIn sivuilla:

Toinen artikkeli, “Pyhän lapsuuden paljastama tabu : näkökulma Sami Saramäen Tom of Finland -muumeihin ja Dana Schutzin Open Casket -maalaukseen,” on puolestaan näkökulma kahteen keväällä 2017 pilkahtaneeseen kuvakiistaan. Sekä huhtikuun Image-lehden “Moomin of Finland” -tapausta, joissa muumihahmot kohahduttivat Sami Saramäen piirtämissä kansikuvissa Tom of Finland-henkisinä, että Dana Schutzin kevään Whitney biennaalissa esitettyä, rodullista väkivaltaa kommentoinutta maalausta Open Casket (2016) yhdisti lapsen figuuri, johon olen väitöskirjassani ankkuroinut tabua. Artikkeli on luettavissa avoimesti verkossa, täällä TAHITIn sivuilla: